December 20, 2008

Messiaen and Beckett: CONCERT:NOVA Contrasts Hope and Despair

In addition, it marked, to my knowledge, the only observation of the centennial of French composer Olivier Messiaen to take place in Cincinnati this year.

Born 100 years ago December 10, Messiaen wrote his famous “Quartet for the End of Time” while interned in a German prisoner of war camp during World War II. It was premiered at Stalag VIII-A in Görlitz, Germany (now Poland) for an audience of fellow prisoners and guards in January, 1941. Informed by the composer’s deep religious faith, it takes the side of hope in a dismal, hope-less world.

CONCERT:NOVA members Ixi Chen (clarinet), Tatiana Berman (violin), Theodore Nelson (cello) and Julie Spangler (piano) performed Messiaen's Quartet along with spoken excerpts from Irish writer/playwright Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” delivered with presence and conviction by Cincinnati actress Julianna Bloodgood. Beckett’s 20th-century classic takes a despairing view of the world, i.e. there is really nothing to hope for.

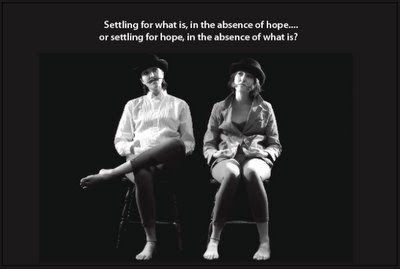

The powerful visual element was created by photographer/visual artist Trinidad Mac-Auliffe who compiled images of Bloodgood as each of the four main characters in the play to be projected simultaneously with the music. The black-and-white photos (taken during a 12-hour photo shoot, said Bloodgood) presented the actress in various combinations of clothing, facial hair and headgear.

Written in 1948-49 (originally in French), “Waiting for Godot” is a two-act play about two friends (Vladimir and Estragon) waiting beside a tree for someone named Godot. They do not actually know Godot, but they have been told to meet him and somehow feel that it is important. They wait for two acts, during which a pair named Pozzo and Lucky (master and slave) drop by. At the end of both acts, a mysterious Boy tells them Godot has been delayed but will come the next day. They pass the time aimlessly with chat and mundane matters, even contemplating suicide as a release from boredom.

By contrast, Messiaen’s Quartet was suggested by passages from chapter 10 of the Book of Revelation where an angel proclaims “that there should be time no longer” and that “the mystery of God should be finished.” The eight movements are correlated to the biblical text. Four are for the full quartet, one for solo clarinet, one each for cello and piano and violin and piano, one for a trio of violin, cello and clarinet. The whole lasts about 48 minutes. Bloodgood and members of C:N dressed in tones of cream and white. The spacious interior of the church, with its warm-wood fittings, stained glass windows, massive cross hanging over the nave, seasonal evergreens and poinsettias, was a thoroughly fitting and gracious venue for the concert.

The opening “Liturgy of Crystal” contrasted the pre-dawn awakening of birds (clarinet and violin against a shimmering background) with images of Estragon trying to remove his boots (“Together again,” comments Vladimir). Vladimir peered into his hat (his thoughts) and Estragon fell asleep during “Vocalise for the Angel who announces the End of Time,” where the quartet gave powerful imagery to the biblical vision of the seventh angel who “set his right foot upon the sea and his left foot on the earth.”

Clarinetist Ixi Chen created incredible sonorities in “Abyss of the Birds,” a moving, eight-minute meditation on (according to Messiaen’s notes for the work) “the sadness” and “weariness” of Time. A feat for the clarinetist, it calls for extremes of pitch and dynamics. Meanwhile on the video screen, Pozzo and Lucky appeared, Pozzo ate chicken and philosophized with Vladimir.

Cellist Nelson soared in “Praise to the Eternity of Jesus,” one of two movements exalting the attributes of Christ. Meanwhile, Bloodgood gave voice to a trivial spat between the waiting pair, who make up and conclude “What do we do now that we are happy? Wait for Godot.” The tree (a symbol of the Cross?) has sprouted leaves in act II of the play, from which Bloodgood interpolated further abstracts to “Dance of Fury, for the Seven Trumpets,” a rhythmically complex and strenuous movement where the quartet emulated apocalyptic sounds.

In the penultimate “Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time,” music from the second movement recurred, as did Pozzo and Lucky on the video screen. Pozzo is now blind, subservient to Lucky and in need of help. Vladimir wrestles with aiding him but concludes “What are we doing here . . . waiting for Godot.” The C:N musicians crafted vivid colors and effects here, from the rich, emotive sound of the instruments in unison to steely arpeggios by violinist Berman and passionate trills by all (as Pozzo and Lucky exited).

It was Berman’s moment in the final movement, “Praise to the Immortality of Jesus,” and she rose to it splendidly. The music paints the soul’s ascent to heaven (compare the composer’s “L’Ascension”), an eight-minute exercise that finishes in stratospheric heights on the violin. Berman has the ability to play with the deepest intensity while avoiding any hint of shrillness or diminishing the beauty of her sound, which blended with the beauty of the cathedral itself.

Bloodgood drew the musicians into the play after the music ended by giving them Vladimir and Estragon’s final words after being told that Godot is again not coming, but will come the day after: Vladimir: “Shall we go?” Estragon: “Yes, let’s go,” followed by lights out and no movement at all.

CONCERT:NOVA L to R: Owen Lee, Tatiana Berman, Patrick Schleker, Mauricio Aguiar, Heidi Yenney, Cristian Ganicenco, Christine Coletta, Randolph Bowman, Ixi Chen, Elizabeth Freimuth, Eric Bates |

For information, visit http://www.concertnova.com/